Asthma is a common disease and its frequency sometimes detracts from its potential seriousness. Severe asthma in children is the third most common cause of hospital admission and the most common cause of paediatric intensive care unit (ICU) admission. In adult asthmatics, only 5-10% have severe disease but these individuals carry a substantial proportion of the cost (both in terms of morbidity and economic consideration) and run the highest risk of acute severe exacerbations and death

Status asthmaticus is severe asthma that does not respond well to immediate care and is a life-threatening medical emergency. Ensuing respiratory failure results in hypoxia, carbon dioxide retention and acidosis. The exact mechanism underlying the development of an acute severe asthma attack remains elusive but there appear to be two phenotypes:

· Gradual-onset - in about 80%, severe attacks develop over more than 48 hours. These are associated with eosinophilic infiltration and slow response to therapy.

· Sudden-onset - often in association with significant allergen exposure. Patients tend to be older and to present between midnight and 8 am. This type of attack is associated with neutrophilic inflammation and a swifter response to therapy.

In deaths from asthma there is often a failure to recognise the full severity of the situation. This can be down to the patient, their family/carers or the healthcare team but often a multitude of factors is involved. Patients frequently have adverse psychosocial factors that interact with the ability to judge or manage their disease or have a diminished perception of their dyspnoea that leads to late presentation. Medical care continues to fail sometimes to treat acute severe asthma aggressively enough or to comply with national guidelines

· Every emergency consultation for asthma should be regarded as for acute severe asthma* until proven otherwise.

· All patients with acute severe asthma* that has not responded to immediate treatment or life-threatening asthma* must be referred to hospital.

*See below for clinical features

Epidemiology

· There were over 79,800 emergency hospital admissions for asthma in the UK in 2008-2009. Of these, 30,740 were children aged 14 years or under.

· There were 1,131 deaths from asthma in the UK in 2009 (12 were children aged 14 years or under).

· An estimated 75% of admissions for asthma are avoidable and as many as 90% of the deaths from asthma are thought to be preventable.

Risk factors

Risk factors for asthma-related death include

· A background disease pattern of chronic severe asthma.

Severe asthma:

o Previous near-fatal asthma.

o Previous admission for asthma, especially in the preceding year.

o Three or more classes of asthma medication.

o Heavy or increasing use of beta2 agonists.

o Frequent emergency contacts for asthma care, especially in the preceding year.

o 'Brittle' asthma.

· Inadequately treated disease +/- inadequate medical monitoring.

· Inappropriate beta-blocker prescription or heavy sedation.

· Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory sensitivity.

· Use of a long-acting beta2 agonist such as salmeterol, especially if not using a steroid inhaler

· Personal or passive smoking.

· Environmental conditions - air pollution (ozone, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and particulates) and pollen levels are thought to influence the rate of hospital admissions.

· Sensitivity to fungi (see 'Severe asthma with fungal sensitisation (SAFS)', below).

· Adverse behavioural/psychosocial factors:

o Non-compliance, frequent failure to attend appointments, self-discharge, denial of illness.

o Psychiatric illness (psychosis, depression, deliberate self harm), alcohol or street drug use.

o Obesity.

o Learning difficulties.

o Employment problems, income problems, social isolation.

o Childhood abuse.

o Severe domestic, marital or legal stress factors.

· Seasonal variation (in the UK, the peak of deaths in those aged under 44 years is in July-August and, in older patients, December-January).

· Pregnancy will exacerbate asthma in about a third of affected women. Treat the asthma - medication should be continued/stepped up where necessary; it is a lesser risk to the fetus than uncontrolled asthma or severe exacerbations.

Severe asthma with fungal sensitisation (SAFS)

Severe asthma may be caused by sensitisation to fungi. See also separate article Aspergillosis for further details regarding allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and SAFS.

· SAFS refers to patients with severe asthma (despite standard treatment) with evidence of fungal sensitisation who do not meet the criteria for ABPA. The total IgE is usually lower than for patients with ABPA ( total IgE <1000 IU/mL).

· Most affected patients only react to one of two fungi, most often Aspergillus fumigatus or Candida albicans.

· Patients with SAFS usually suffer with chronic severe asthma symptoms despite maximal treatment, including steroids.

· Treatment of SAFS should initially be similar to that of severe asthma

· Antifungal therapy with itraconazole is beneficial (fluconazole may be beneficial in those sensitised to Trichophyton spp.). The duration of antifungal therapy required is not yet fully established

Presentation

Symptoms

· Shortness of breath may develop over hours or days but is usually progressive rather than sudden.

· A history of poor control is common.

· Often there has been a recent increase in use of reliever inhalers, with decreasing response.

· Possible respiratory tract infection or exposure to an allergen or trigger.

Signs

· The patient will usually appear pink. Cyanosis is a serious sign.

· Their respiratory rate is raised.

· Tachycardia is usual and may be increased by use of beta2 agonists.

· Accessory muscles of respiration are employed (best assessed by palpation of the neck muscles) and the chest appears hyper-inflated.

· In normal breathing, the ratio of the duration of inspiration to expiration is about 1:2 but, as asthma becomes more severe, the expiratory phase becomes relatively more prolonged.

· Wheeze is usually expiratory, but may also be inspiratory in more severe asthma.

Pitfalls:

o A very tight chest may not wheeze at all due to poor air entry. Beware the silent chest.

o Patients with severe or life-threatening asthma may not appear distressed.

o The presence of any relevant abnormality should alert the doctor.

o Where signs/symptoms cross categories of severity, always assign the most severe category.

· Pulsus paradoxus is no longer recommended as a reliable indicator of the severity of an asthma attack.

Differential diagnosis

Status asthmaticus must be distinguished from other causes of acute breathlessness, including:

· Wheezing in children, which can be caused by a variety of infective conditions, eg respiratory syncytial virus-causing bronchiolitis.

· Foreign body inhalation and other causes of stridor (eg epiglottitis, croup, tracheitis, vascular ring, tracheomalacia, etc.).

· Allergic reaction, anaphylaxis

· Primary pulmonary hypertension.

· Pneumothorax with or without asthma.

· Inhalation injury.

· Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

· Bronchiectasis.

· Lung cancer.

· Cardiac failure ('cardiac asthma').

PatientPlus o

· Bronchial Asthma

· Management of Childhood Asthma

· Management of Adult Asthma

· Peak Flow Recording

Management

Initial assessment

· Take a very quick history and brief examination (conscious level, colour, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, listening to chest, etc.).

· Supplement with objective bedside investigations if available:

o Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) - this can be useful as an objective measurement and should be attempted with adults, and children aged over 5 years, but can be unreliable due to distress or poor co-operation. PEFR should be compared with a personal best PEFR done within the previous two years and when clinically well controlled.

o Pulse oximetry - a good quick measure of oxygenation.

Assessment of severity

If a patient has signs and symptoms across categories, always treat according to their most severe features.

Adults

· Moderate asthma exacerbation:

o Increasing symptoms.

o PEFR >50-75% best or predicted.

o No features of acute severe asthma.

· Acute severe asthma - any one of:

o PEFR 33-50% best or predicted.

o Respiratory rate ≥25 breaths/minute.

o Heart rate ≥110 beats/minute.

o Inability to complete sentences in one breath.

· Life-threatening asthma - any one of the following in a patient with severe asthma:

o Clinical signs: altered conscious level, exhaustion, arrhythmia, hypotension, cyanosis, silent chest, poor respiratory effort.

o Measurements: PEFR <33% best or predicted, SpO2 <92%, PaO2 <8 kPa, 'normal' PaCO2 (4.6-6.0 kPa).

Children aged over 2 years

· Moderate asthma exacerbation:

o Able to talk in sentences.

o SpO2 ≥92%.

o PEFR ≥50% best or predicted.

o Heart rate ≤140 beats/minute in children aged 2-5 years; ≤125/minute in children >5 years.

o Respiratory rate ≤40 breaths/minute in children aged 2-5 years; ≤30 breaths/minute in children >5 years.

· Acute severe asthma:

o Can't complete sentences in one breath or too breathless to talk or feed.

o SpO2 <92%.

o PEFR 33-50% best or predicted.

o Pulse >140 in children aged 2-5 years; >125 in children aged >5 years.

o Respiratory rate >40 breaths/minute aged 2-5 years; >30 breaths/minute aged >5 years.

· Life-threatening asthma - any one of the following in a child with severe asthma:

o Clinical signs: silent chest, cyanosis, poor respiratory effort, hypotension, exhaustion, confusion.

o Measurements: SpO2 <92%, PEFR <33% best or predicted.

Infants and toddlers aged under 2 years

· The assessment of acute asthma in early childhood can be difficult.

· Most infants are audibly wheezy with intercostal recession but not distressed.

· Life-threatening features include apnoea, bradycardia and poor respiratory effort.

· Moderate: SpO2 ≥92%, audible wheezing, using accessory muscles, still feeding.

· Severe: SpO2 <92%, cyanosis, marked respiratory distress, too breathless to feed.

Initial treatment

· Consider the need for immediate transfer to hospital - arrange 999 ambulance.

· Give supplementary oxygen to all hypoxaemic patients with acute severe asthma to maintain an SpO2 level of 94-98%. Lack of pulse oximetry should not prevent the use of oxygen.

· Beta2 agonist bronchodilators:

o Outside hospital, high-dose beta2 agonists may be given via large spacer devices (4-10 puffs inhaled individually) or nebulisers once available (this should be oxygen-driven where available). Repeat doses of beta2 agonists at 15- to 30-minute intervals. There is no evidence for any difference in efficacy between salbutamol and terbutaline.

o Higher bolus doses, eg 10 mg of salbutamol, are unlikely to be more effective.

o Reserve intravenous beta2 for those patients in whom inhaled therapy cannot be used reliably.

o For adults with severe asthma that is poorly responsive to an initial bolus dose of beta2, consider continuous nebulisation of salbutamol at 5-10 mg/hour with an appropriate nebuliser. Continuous nebulised beta2 agonists are of no greater benefit than the use of frequent intermittent doses in the treatment of children with acute asthma.

· Ipratropium bromide:

o Add nebulised ipratropium bromide (0.5 mg 4-6-hourly) to beta2 agonist treatment for adults with acute severe or life-threatening asthma, or those with a poor initial response to beta2 agonist therapy.

o Children: frequent doses of ipratropium bromide up to every 20-30 minutes (250 micrograms/dose mixed with 5 mg of salbutamol solution in the same nebuliser) should be used for the first few hours of admission. The salbutamol dose should then be weaned to 1-2-hourly according to clinical response and the ipratropium dose should be weaned to 4-6-hourly or discontinued.

· Corticosteroids:

o Corticosteroids reduce mortality and should be given as early in the acute attack as possible. Give steroids in adequate doses in all cases of acute asthma. Steroid tablets are as effective as injected steroids, provided they can be swallowed and retained.

o Give oral prednisolone (10 mg if aged <2, 20 mg if aged 2-5, 30-40 mg in older children and 40-50 mg in adults). If unable to retain oral medication, give hydrocortisone 100 mg IV (4 mg/kg for children) 6-hourly. Higher doses of steroids don't appear to have any advantage.

o For adults, continue prednisolone 40-50 mg daily for at least five days or until recovery. Treatment for up to three days is usually sufficient for children but the duration of treatment will depend on the length of time to recovery.

· Consider giving a single dose of IV magnesium sulphate for patients with with life-threatening or near-fatal asthma, or with acute severe asthma who have not had a good initial response to inhaled bronchodilator therapy.

· Antibiotics are not routinely indicated.

Infant and toddlers aged under 2 years

· Require urgent admission to hospital.

· Oxygen via close fitting face mask or nasal prongs to achieve normal saturations.

· Give trial of beta2 agonist: salbutamol up to 10 puffs via spacer and face mask or nebulised salbutamol 2.5 mg or nebulised terbutaline 5 mg.

· Repeat beta2 agonist every 1-4 hours if responding.

· If poor response: add nebulised ipratropium bromide 0.25 mg.

· Consider: soluble prednisolone 10 mg daily for up to three days.

· Continuous close monitoring: heart rate, pulse rate, pulse oximetry; supportive nursing care with adequate hydration, consider the need for a chest X-ray.

Referral

Criteria for admission

· Any feature of life-threatening or near-fatal attack.

· Any feature of severe attack persisting after initial treatment.

· Patients with PEFR >75% best or predicted, one hour after initial treatment but where:

o There are significant symptoms.

o There are concerns about compliance.

o The patient is socially isolated/lives alone.

o Psychological problems exist.

o There is physical disability or learning difficulties exist.

o There is previous near-fatal or brittle asthma.

o There has been exacerbation despite the adequate dose of oral steroid tablets prior to presentation.

o Presentation is at night.

o Pregnancy.

When admitting

· Arrange a 999 ambulance if there is any feature of life-threatening or worsening acute severe asthma.

· Stay with the patient until the ambulance arrives. Maintaining calm in the patient and their family is very important - patients with acute asthma are often highly anxious and getting a small child to accept treatment via a noisy nebuliser or facemask-based device may be challenging.

· Continue treating (high-dose short-acting beta2 agonist via oxygen-driven nebuliser) and regularly reassessing the patient (at least every 15 minutes) until the transfer to hospital has been achieved.

· Send written assessment and referral details with the patient.

Further hospital-based management

Monitoring and investigations

· Continue regular monitoring - PEFR following nebulised or inhaled beta2 agonists, continuous oxygen saturation monitoring, pulse, respiratory rate.

· Blood tests - FBC, serum potassium and glucose, serum theophylline (where aminophylline is used for more than 24 hours).

· Arterial blood gases should be checked where there are life-threatening features. The four stages of blood gas progression in status asthmaticus are as follows:

o The first stage is characterised by hyperventilation with a normal pO2 and low pCO2.

o The second stage has hyperventilation but hypoxaemia so that both pO2 and pCO2 are low.

o The third stage gives a 'false-normal' pCO2 as ventilation has decreased. This is extremely serious and indicates respiratory muscle fatigue with the need for admission to the ICU and, probably, intubation with mechanical ventilation.

o The fourth stage has a low pO2 and a high pCO2 as respiratory muscles fail.

Repeat blood gases within two hours of starting treatment when:

o The initial pO2 is <8 kPa unless SaO2 is >92%.

o The initial pCO2 is normal or raised.

o The patient's condition deteriorates.

o The third and fourth stages require admission to ICU.

· Consider the need for CXR - routine use is not recommended but it may be used to exclude consolidation or pneumothorax and is needed prior to mechanical ventilation.

Further hospital treatment

· IV fluids where the patient is dehydrated and correction of hypokalaemia (caused/exacerbated by beta2 agonist and steroid regimes).

· IV aminophylline - this is only used in patients with near-fatal or life-threatening asthma with poor response to initial treatment, after consultation with senior staff. Side-effects, eg arrhythmias and vomiting, increase with its use.

· Where patients are failing to respond to treatment, they require transfer to ICU or high-dependency unit (HDU) conditions.

· Those with worsening hypoxia, hypercapnia, drowsiness or unconsciousness and those experiencing a respiratory arrest require intubation. This is technically difficult and and should be undertaken by an anaesthetist or ICU consultant.

· The use of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in status asthmaticus remains controversial.[12]

· Evidence on the efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty for severe asthma shows some improvement in symptoms and quality of life, and reduced exacerbations and admission to hospital.[13]

Support groups e

· EFA - European Federation of Asthma and Allergy Association

· Asthma UK

Find support near you ▶

Complications

Complications of status asthmaticus include:

· Aspiration pneumonia.

· Pneumomediastinum.

· Pneumothorax.

· Rhabdomyolysis.

· Respiratory failure and arrest.

· Cardiac arrest.

· Hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury.

· Death.

In one study of children admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), there was a 22% complication rate, increased by intubation. The risk of death is increased where there is delay in getting treatment, particularly time to starting steroids, comorbidities such as congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and in smokers. Mortality is highest in the very young and the very old.

Prevention

· All patients with asthma, but especially those with poorly controlled disease, should have access to education about their condition and to regular review, and should have an asthma action plan.

· In addition to an asthma register, an 'at-risk' asthma register may help. If 'at-risk' patients fail to attend for appointments this should be actively followed up.

· Those who are difficult to control need referral to specialist services.

· Be especially vigilant about those with psychosocial adverse factors too.

· Beta2 agonist therapy used in isolation is only appropriate for those with the mildest variant of asthma.

· Receptionists, ambulance control workers and those who are first point of contact by patients must appreciate that an asthmatic having difficulty breathing needs to be seen as an emergency.

· Hospital admission should be an opportunity to review the patient's care plan.

· Anyone who has required admission should be followed up by a respiratory physician for at least a year.

· Patients who have had near-fatal asthma or brittle asthma should remain under specialist care indefinitely.

Provide Feedback

Further reading & references

· Primary Care Respiratory Society UK (PRCS)

· Saadeh CK, Status Asthmaticus, Medscape, Mar 2011

· Schwarz AJ, Pediatric Status Asthmaticus, Medscape, Oct 2011

1. Mannix R, Bachur R; Status asthmaticus in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007 Jun;19(3):281-7.

2. Carroll CL, Zucker AR; The increased cost of complications in children with status asthmaticus. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007 Oct;42(10):914-9.

3. Holgate ST, Polosa R; The mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 2006 Aug 26;368(9537):780-93.

4. Restrepo RD, Peters J; Near-fatal asthma: recognition and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008 Jan;14(1):13-23.

5. Ramnath VR, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr; Multicenter study of clinical features of sudden-onset versus slower-onset asthma exacerbations requiring hospitalization. Respir Care. 2007 Aug;52(8):1013-20.

6. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma; British Thoracic Society (BTS) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines (SIGN), 2008

7. Key facts and statistics; Asthma UK

8. Hancox RJ; Concluding remarks: can we explain the association of beta-agonists with asthma mortality? A hypothesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2006 Oct-Dec;31(2-3):279-88.

9. Hogan C, Denning DW; Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and related allergic syndromes. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Dec;32(6):682-92. Epub 2011 Dec 13.

10. Agarwal R; Severe asthma with fungal sensitization. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011 Oct;11(5):403-13.

11. Denning DW, O'Driscoll BR, Powell G, et al; Randomized controlled trial of oral antifungal treatment for severe asthma with Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Jan 1;179(1):11-8. Epub 2008 Oct 23.

12. Ram FS, Wellington S, Rowe B, et al; Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for treatment of respiratory failure due to severe acute exacerbations of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jul 20;(3):CD004360.

13. Bronchial thermoplasty for severe asthma, NICE Interventional Procedure Guideline (January 2012)

14. Harrison B, Stephenson P, Mohan G, et al; An ongoing Confidential Enquiry into asthma deaths in the Eastern Region of the UK, 2001-2003. Prim Care Respir J. 2005 Dec;14(6):303-13. Epub 2005 Oct 11.

Severe Asthma Attacks

*******************

Signs of a Pending Asthma Attack

An acute, severe asthma attack that doesn't respond to usual use of inhaled bronchodilators and is associated with symptoms of potential respiratory failure is called status asthmaticus. This is life-threatening and requires immediate medical attention. It is important to be aware of these severe asthma attacks and prevent them with early intervention.

What Are The Symptoms of a Severe Asthma Attack?

The symptoms of a severe asthma attack may include:

· Persistent shortness of breath

· The inability to speak in full sentences

· Breathlessness even while lying down

· Chest that feels closed

· Bluish tint to your lips

· Agitation, confusion, or an inability to concentrate

· Hunched shoulders and strained abdominal and neck muscles

· A need to sit or stand up to breathe more easily

These are signs of an impending respiratory system failure and require immediate medical attention.

You may not have more wheezing and coughing with a severe asthma attack. In fact, the presence of wheezing or coughing is not a reliable standard for judging the severity of an asthma attack. Very severe asthma attacks may affect airways so much that the lack of air in and out of your lungs does not cause a wheezing sound or coughing.

Are There Warning Signs of a Severe Asthma Attack?

A severe asthma attack often occurs with few warning signs. It can happen quickly and progress rapidly to asphyxiation.

Does Wheezing Indicate a Severe Asthma Attack?

Wheezing does not necessarily indicate asthma. Wheezing can also be a sign of other health conditions, such as respiratory infection, heart failure, and other serious problems.

What Causes a Severe Asthma Attack?

Whereas the causes of an acute, severe asthma attack are unknown, those people who have them may have a history of infrequent health care, which may result in poor treatment of asthma.

Some research shows that people who are at risk for a severe asthma attack have poor control of allergens or asthma triggers in the home and/or workplace. These people may also infrequently use their peak flow meter and inhaled corticosteroids. Inhaled steroids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs that are highly effective in reducing inflammation associated with asthma.

To prevent a severe asthma attack, it is important to monitor your lung function using a peak flow meter regularly and take your asthma medication as recommended by your health care provider.

How Is a Severe Asthma Attack Diagnosed?

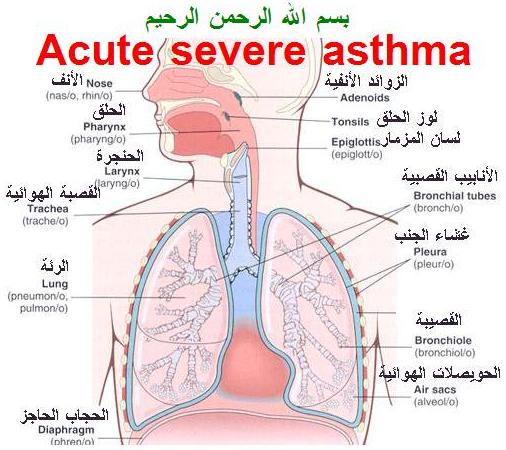

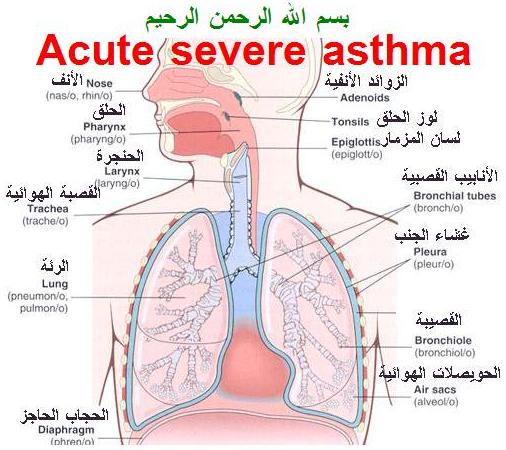

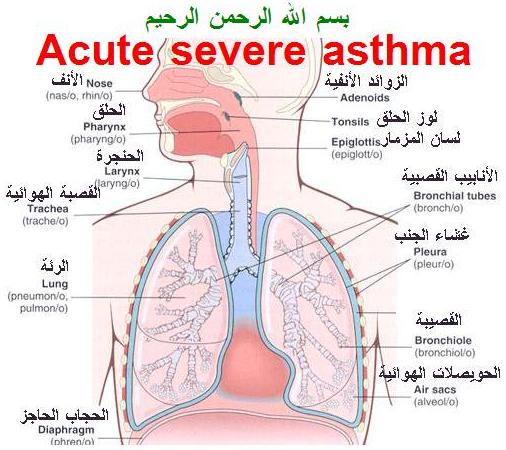

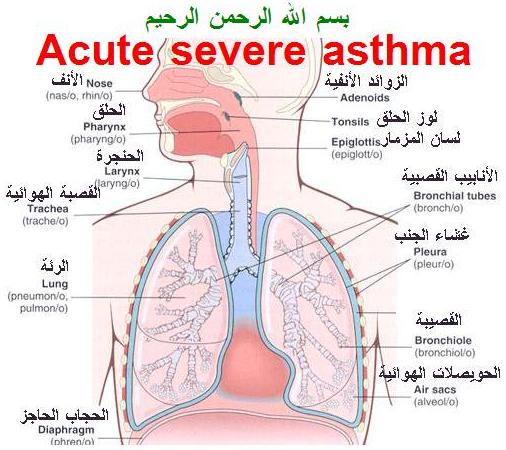

To diagnose a severe asthma attack as actual status asthmaticus, your doctor will notice physical findings such as your consciousness, fatigue, and the use of accessory muscles of breathing. Your doctor will notice your respiration rate, wheezing during both inhalation and exhalation, and your pulse rate. Some other tests may include peak expiratory flow and oxygen saturation, among others. Other physical symptoms will be noticed with the chest, mouth, pharynx, and upper airway.

Acute severe asthma

Acute severe asthma previously referred to as status asthmaticus is an acute exacerbation of asthma that does not respond to standard treatments of bronchodilators (inhalers) and steroids.[1] Symptoms include chest tightness, rapidly progressive dyspnea (shortness of breath), dry cough, use of accessory respiratory muscles, labored breathing, and extreme wheezing. It is a life-threatening episode of airway obstruction and is considered a medical emergency. Complications include cardiac and/or respiratory arrest.

It is characterized histologically by smooth muscle hypertrophy and basement membrane thickening.

Contents

· 1 Epidemiology

· 2 Pathophysiology

· 3 Treatment

· 4 References

· 5 External links

Epidemiology

Status asthmaticus is slightly more common in males and is more common among African Americans and Hispanics. The gene locus glutathione dependent S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNOR) has been suggested as one possible correlation to development of status asthmaticus.

Pathophysiology

Inflammation in asthma is characterized by an influx of eosinophils during the early-phase reaction and a mixed cellular infiltrate composed of eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophils during the late-phase (or chronic) reaction. The simple explanation for allergic inflammation in asthma begins with the development of a predominantly helper T2 lymphocyte–driven, as opposed to helper T1 lymphocyte–driven, immune milieu, perhaps caused by certain types of immune stimulation early in life. This is followed by allergen exposure in a genetically susceptible individual.

Specific allergen exposure (e.g., dust mites) under the influence of helper T2 lymphocytes leads to B-lymphocyte elaboration of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies specific to that allergen. The IgE antibody attaches to surface receptors on airway mucosal mast cells. One important question is whether atopic individuals with asthma, in contrast to atopic persons without asthma, have a defect in mucosal integrity that makes them susceptible to penetration of allergens into the mucosa.

Subsequent specific allergen exposure leads to cross-bridging of IgE molecules and activation of mast cells, with elaboration and release of a vast array of mediators. These mediators include histamine; leukotrienes C4, D4, and E4; and a host of cytokines. Together, these mediators cause bronchial smooth muscle constriction, vascular leakage, inflammatory cell recruitment (with further mediator release), and mucous gland secretion. These processes lead to airway obstruction by constriction of the smooth muscles, edema of the airways, influx of inflammatory cells, and formation of intraluminal mucus. In addition, ongoing airway inflammation is thought to cause the airway hyperreactivity characteristic of asthma. The more severe the airway obstruction, the more likely ventilation-perfusion mismatching will result in impaired gas exchange and hypoxemia.

Treatment

Interventions include intravenous (IV) medications, aerosolized medications, and positive-pressure therapy, including mechanical ventilation. Often multiple therapies are used to reverse the effects of status asthmaticus as rapidly as possible; though typically only one or two therapies are ultimately necessary, the permanent or generally long-term damage done by the airway restriction is a concern of clinicians. Intravenous and aerosolized treatments such as corticosteroids, and methylxanthines are often given. Magnesium sulfate is also commonly administered.

References

1. Shah, R; Saltoun, CA (May–Jun 2012). "Chapter 14: Acute severe asthma (status asthmaticus).". Allergy and asthma proceedings : the official journal of regional and state allergy societies. 33 Suppl 1: S47–50. doi:10.2500/aap.2012.33.3547. PMID 22794687.

2. Moore PE, Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Patel N, Summar ML, Sheller JR (9 July 2009). "Genetic variants of GSNOR and ADRB2 influence response to albuterol in African-American children with severe asthma.". Pediatric Pulmonology 44 (7): 649–654. doi:10.1002/ppul.21033. PMID 19514054.

3. Ratto D, Alfaro C, Sipsey J, Glovsky MM, Sharma OP (1988). "Are intravenous corticosteroids required in status asthmaticus?". JAMA 260 (4): 527–9. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410040099036. PMID 3385910.

Acute severe asthma

Acute severe asthma

Acute severe asthma

Acute severe asthma